The 2018 album Avant comes with two PDF-format digital booklets. One has the usual contents: track listings and credits, lyrics, and original art. The second has biographical notes on the artists celebrated in the album’s tracks, links to related material, and more original art. Lyrics that are in French or Portuguese are followed by an English translation.

All the contents of the two booklets can also be found on this page. It has additional features as well, including extra links to related material, the video for “Dada Dance,” and images to accompany some of the artist biographies.

Avant celebrates the avant garde artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who helped to reinvent the way we see and understand the world. Some are well known, like Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dalí, but there’s a special focus on those who were either overlooked at the time or have been largely forgotten since, especially those who may have received less attention, not because of the quality of their work, but because they were women, people of color, or LGBTQ+.

Scroll down for information and images, or use the links below to jump to the section you want.

Tracks and Credits

- (3:03) Dada Dance (for Hannah Höch)

- (3:46) Eve (Welcome to Dream Land) (for Iwata Nakayama)

- (3:08) Une Fièvre Permanente (for Guillaume Apollinaire)

- (3:48) Fuel (for F.T. Marinetti)

- (4:05) Cathedral (It Is Moral If You Can Dance To It) (for Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven)

- (3:08) Every Page (for Tristan Tzara)

- (3:28) La Mariée (for Marcel Duchamp)

- (4:00) Opera (for Zhao Shou)

- (3:35) Ligne Bleu Clair (for Simone Yoyotte)

- (3:16) Sui Generis (for Claude Cahun)

- (3:02) HexenTexte (for Unica Zürn)

- (2:57) C’est L’extase (for Baya Mahieddine)

- (3:08) The Burning Giraffe (for Salvador Dalí)

- (3:27) Daughter of the Minotaur, Part I (A Slow Swamp Strut) (for Leonora Carrington)

- (3:02) Entre Tes Mots (for Jean-Joseph Rabéarivelo)

- (3:16) Le Flâneur Dans La Foule (for Charles Baudelaire)

- (3:01) Canção Do Canibal (for Oswalde de Andrade)

- (2:59) Daughter of the Minotaur, Part II (A Roadhouse Stomp) (for Leonora Carrington)

- (3:12) Piazza Shadows (for Giorgio de Chirico)

- (3:13) Ubu Dit Au Revoir (for Alfred Jarry)

All songs written and recorded by Nas Hedron.

Vocal performances by track:

Tracks 1, 8-13, and 20: all vocals by Ooma Kollectiv.

Tracks 2-7 and 14-19: lead vocals by Nas Hedron, backing vocals by Ooma Kollectiv.

All songs (C) & (P) 2018 Nas Hedron.

All original text and art work (C) 2018 Nas Hedron.

Many thanks to Célio Fioretti for reviewing my French lyrics–any errors that remain are all on me.

Lyrics

1. (3:03) Dada Dance (for Hannah Höch)

Amina miy ounfashe

Ine ounfashe

Ishenok ishenokish.

Tsonayue

Gwiyane sham haye

Gwiyane sonz, sonz, sonz.

Amina miy ounfashe

Ine ounfashe

Ishenok ishenokish.

Shamhaye, iyana shamhaye

Alezimov, alewiy.

There is no translation for this song.

“Dada Dance” Video:

2. (3:47) Eve (Welcome to Dream Land) (for Iwata Nakayama)

Do do do do do

Do do do do.

It’s finally evening

End of the day

Dreams come calling

Take us away.

They come and they go

And they do what they want to.

Welcome to dreamland, welcome to dreamland,

Welcome to dreamland

Welcome. Welcome.

3. (3:09) Une Fièvre Permanente (for Guillaume Apollinaire)

Une fièvre de couleur

Dépouillée de toute douceur

Aussi brillante que le verre—

Ma fièvre brûle la terre,

Brûle la terre.

Il y a de la fièvre

Dans mes yeux

Et je chasse toutes les visions

Que je peux.

Que je peux.

Translation: A Permanent Fever

A fever of color

Stripped of softness

As shiny as glass—

My fever burns the Earth,

burns the Earth.

There’s fever in my eyes

As I hunt all the visions that I can,

That I can.

4. (3:48) Fuel (for F.T. Marinetti)

Tired of everything that came before

Everything old and exhausted

We construct with our own hands

We assemble out of steel, and grease, and gasoline

A new aesthetic, a new idea of pleasure,

Of what gives delight: electricity, fire, pistons

Gears, and valves, and sparks

And, in the flickering light: speed, speed, speed.

And if our machines consume us well

Nothing runs without fuel.

Nothing, nothing.

Nothing runs without fuel.

And if our machines consume us

Well, well, well.

Well, well.

5. (4:05) Cathedral (It Is Moral If You Can Dance To It) (for Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven)

It is moral if it is richly flavored, urgent with life

It is moral if it asserts the future and perfects enjoyment

It is good if it is graceful, quick, and unsentimental

It is good if you can dance to it.

The new commandment is: thou shalt.

Thou shalt.

It is good if you can dance to it.

It is moral if you can dance to it.

It is good if it is colorful.

If it is richly flavored.

If it is urgent with life.

It is good if you can dance to it.

Dance to it.

Dance to it.

6. (3:08) Every Page (for Tristan Tzara)

Huh! Huh huh!

Rah! Rah!

Every page, every page, every puh-page

Every page, every page page page page.

Every page should explode

Every page, every page

Every page should explode

Exp-exp-exp-explode.

Every page should explode…

7. (3:28) La Mariée (for Marcel Duchamp)

J’ai un corps de verre , j’ai un coeur mécanique

Je suis heureux, je suis heureux

Je suis plein de bonheur.

J’ai un coeur de verre, j’ai un corps mécanique

Je danse au soleil

Je suis si romantique.

J’écoute la chanson

Mais j’entends la ville.

J’écoute la chanson

Mais j’entends la pluie.

J’entends, juste à peine, ce que tu dis.

Translation: The Bride

I have a glass body, I have a mechanical heart.

I’m happy, I’m happy

I’m full of good humor.

I have a glass heart, I have a mechanical body.

I dance in the sun

I’m that romantic.

I listen to the song

But I hear the city.

I listen to the song

But I hear the rain.

And I hear, just barely, what you’re saying.

8. (4:00) Opera (for Zhao Shou)

No lyrics.

9. (3:35) Ligne Bleu Clair (for Simone Yoyotte)

No lyrics.

10. (3:16) Sui Generis (for Claude Cahun)

She is always the woman.

The most perfect machine.

She’s singular, precise.

And she’s sex.

Hmmm.

She’s a mask, a mystery.

And she is the woman.

The woman.

11.(3:02) HexenTexte (for Unica Zürn)

No lyrics.

12. (2:57) C’est L’extase (for Baya Mahieddine)

C’est l’extase?

C’est l’extase.

Cette âme

En flammes.

Et ma raison

Chante ma chanson..

C’est l’extase?

C’est l’extase.

C’est l’extase.

Translation: This is Ecstasy

This is ecstasy?

This is ecstasy.

This soul

In flames.

And my reason

Sings my song.

This is ecstasy?

This is ecstasy.

This is ecstasy.

13. (3:08) The Burning Giraffe (for Salvador Dalí)

No lyrics.

14. (3:27) Daughter of the Minotaur, Part I (A Slow Swamp Strut) (for Leonora Carrington)

She said:

Here is where I was born

In the wood

In the vast wood.

And in the rain that fell, my mother exulted.

I have seen it, glimpses—

In my dreams, in my ecstasies.

And here is also where

My mother died, that very night.

There’s the grave

Profound and secret.

Wildflower and wood

Wildflower and my mother.

Wildflower and wood

Wildflower and my mother.

15.(3:02) Entre Tes Mots (for Jean-Joseph Rabéarivelo)

Je me glisse

Entre tes mots

Entre les feuilles

Entre les sons.

Je perds le chemin

Les étoiles

Toutes les cartes.

Ici je suis perdu

Et ici je me retrouve—

Chez moi encore.

Translation: Between Your Words

I slip

Between your words

Between the leaves

Between the sounds.

I lose the path

The stars

All the maps.

Here, I’m lost

And here I rediscover myself—

At home once more.

16.(3:16) Le Flâneur Dans La Foule (for Charles Baudelaire)

Dans le courant de la foule

Au milieu de cent remous

Dans ce monde d’instantané

Je touche mais je ne suis pas touché.

Je vois, mais je ne suis pas vu

Dans la foule si chaude et douce

Sur ma langue il y a le goût

D’humanité et ses tabous.

La foule est une chose vivante

Énergique et captivante

La foule poursuit et la foule chasse

Dévore la vie, laisse la carcasse.

Translation: The Flâneur In The Crowd

In the current of the crowd

In the middle of a hundred eddies

In this world of the snapshot

I touch but I’m not touched.

I see, but I’m not seen

In the crowd so hot and sweet.

On my tongue there is the taste

Of humanity and its taboos.

The crowd is a living thing

Energetic and captivating

The crowd pursues and the crowd hunts

Devours life, leaving the carcass.

17.(3:01) Canção Do Canibal (for Oswalde de Andrade)

Barulho! E bagunça! E banalidade.

Intolerável!

Devemos engolir o mundo

Nossas próprias paixões

Fazer o novo mundo.

Barulho! E bagunca! E banalidade.

Translation: The Cannibal Song

Noise! And mess! And banality.

Intolerable!

We must swallow the world

Our own passions

Make the new world.

Noise! And mess! And banality.

18. (2:59) Daughter of the Minotaur, Part II (A Roadhouse Stomp) (for Leonora Carrington)

She looked at me—

she looked at me and she said:

It’s the runoff from the abattoir that waters this grove

What blooms up above is what’s planted below.

What sinks in the shadows, flows in the root

And the sugar in the dark makes for sweeter fruit.

Life’s too short to be ordinary.

The water here is shallow, but the woods are deep

And no one here bothers about the company you keep.

You come here to visit, but I know you’ll stay

All the swamp folk get started that way.

Life’s too short.

Life’s too short.

Too short, too short.

19. (3:12) Piazza Shadows (for Giorgio de Chirico)

One I pick up

One I put down

One I pick up

One I let go.

Piazza shadows

Cling to the walls.

Memory shadows

Childhood calls.

Shadows.

Shadows.

20. (3:13) Ubu Dit Au Revoir (for Alfred Jarry)

I am fiction, I am thee.

I am fiction, I am free.

I am fiction, I am free.

It must be: beauty and perfection

It must be: endless variety

It must be: richness and

richness and

richness and splendor.

I am unbroken

And free.

Biographical Notes on the Artists

1. Dada Dance

Hannah Höch (Germany, 1889–1978) Wikipedia Link

Hannah Höch was one of the originators of the photomontage and is particularly associated with the dada artists of the Weimar Republic in Germany. The dadaists prized irrationality, instinct, and accident, creating fertile ground for all forms of collage and the assembly. Höch worked for years on commercial women’s magazines featuring dresses, embroidery, and lace, making this kind of illustration a natural source for her work. Her art was featured at the First International Dada Fair in 1920, and was not only technically innovative, but broadly liberationist, critiquing mass culture, commercialism, sexism, and racism.

This track is named for her photomontage, Dada Dance (1921), below.

2. Eve (Welcome to Dream Land)

Iwata Nakayama (Japan, 1895-1949) Wikipedia Link

Iwata Nakayama was a pioneering surrealist photographer. Born in Japan, he was educated there and in the U.S., then relocated to Paris, where he got to know surrealist photographer Man Ray. He resettled in Japan in 1927, where he taught photography and published his work. In 1930, he was a founding member of the Ashiya Camera Club, which became the main force behind “New Photography” in Japan, and in 1932 he and two other photographers began the influential art photography monthly, Kōga. He died in 1949, aged only fifty-four.

This track is named for his image, Eve (1940), whose title I’ve chosen to interpret as referring to both the time of day, the evening, and the proper name, Eve.

You can see Nakayama’s Eve here.

3. Une Fièvre Permanente

Guillaume Apollinaire (France, 1880-1918) Wikipedia Link

Wilhelm Albert Vladimir Apollonaris de Kostrowicki, who adopted the name Guillaume Apollinaire, was born in Italy to a Polish noblewoman (and an undetermined father), but ultimately settled in France. A playwright, poet, and novelist, he invented the term “surrealism.” He made his reputation with the 1913 poetry collection Alcools (“Alcohols“), and is also widely known for the concrete poetry of 1918’s Calligrammes, in which a poem’s appearance—its typography and layout—is an integral part of the work. Apollinaire suffered a head wound in World War I in 1916 from which he never fully recovered, eventually dying in the great flu epidemic of 1918.

The title of this track refers to the literal fever of the flu that killed Apollinaire, but also to the imaginative fever in which he lived his artistic life.

Apollinaire with his war wound (right) and one of his Calligrammes (left).

4. Fuel

F.T. Marinetti (Italy, 1876-1944) Wikipedia Link

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was an Italian poet and art theorist. He is best known as the author of the Manifesto of Futurism (1909) and as a founder of futurism, an art movement that rejected the past and celebrated futuristic notions of speed, mechanization, and unsentimentality. He also aligned himself with nationalism and fascism, aspects of his outlook for which he is justifiably condemned, but his immense talent is undeniable, as is his persistent—even growing—relevance in an era of rapid technological change.

This track references the images and ideas in Marinetti’s manifesto, and in particular his declaration of “una bellezza nuova; la bellezza della velocità” (“a new beauty; the beauty of speed”).

Marinetti about 1915 (center), his Futurist Manifesto of 1909, in French (left), and a copy of his sound poem “Zang Tumb Tumb” (right).

5. Cathedral (It Is Moral If You Can Dance To It)

Elsa Hildegard Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (Germany, 1874-1927) Wikipedia Link

Elsa Hildegard Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven was a German artist who worked in collage, performance, and assemblage, as well as writing poetry. She did much of her important work while living in New York City, and she is often referred to as the first American dadaist. She was widely known for the elaborate costumes she would create and then wear in public, made from everyday objects, and for creating many readymade artworks (objects that already exist, which the artist finds and designates as art). Some historians have claimed that Fountain, the readymade urinal attributed to her friend, Marcel Duchamp, was actually her work. A collection of her poetry, Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, was published in 2011.

This track is named for her readymade sculpture, Cathedral (1918), which consists of a found fragment of weathered wood with a spire-like shape.

The Baroness with Jamaican novelist and poet Claude McKay (left) and her Cathedral (right).

6. Every Page

Tristan Tzara (Romania, 1896-1963) Wikipedia Link

Tzara came from Romania, but later moved to the artistic hub of Paris. As the author of several dada manifestos, he was one of the founders of the movement, and later an important figure in surrealism. His insight and inventiveness have meant that he’s rediscovered and reinterpreted by successive generations of artists, while his confrontational style has made him a favorite in subcultures from the beats to punk. His “How to Make a Dadaist Poem,” applied collage techniques to written text, anticipating the cutup method later used so effectively by William Burroughs, and David Bowie expressly paid tribute to Tzara when using the technique in his songwriting. More recently, his voice was remixed, along with those of other avant garde artists, in DJ Spooky’s book/CD Rhythm Science (2004).

This composition takes its name from a phrase in his Dada Manifesto (1918), published in issue #3 of Dada, below. You can download free PDFs of all issues of Dada here (click on the “download” link–clicking on the cover just gets you… an image of the cover).

Tzara (left) and issue #3 of Dada, which contained his Dada Manifesto of 1918.

7. The Bride

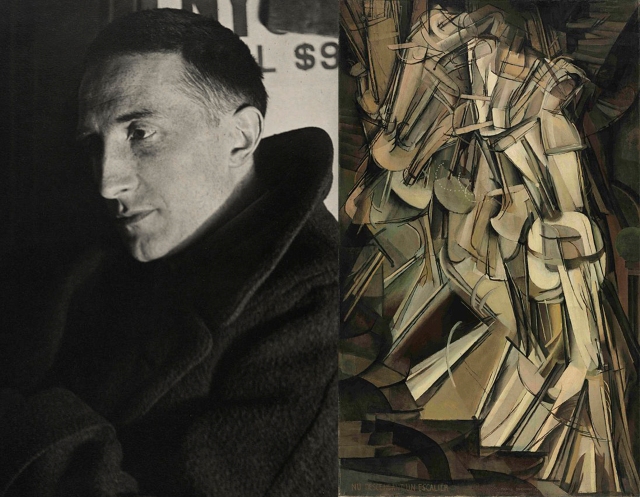

Marcel Duchamp (France, 1887-1968) Wikipedia Link

Duchamp was a French painter, sculptor, and writer, who also spent long periods of time in New York City. One of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, two of his best known works are Fountain, (see Track 6), and La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even). Duchamp began as a painter, but was later a principal proponent of the readymade. He also created kinetic works (art with moving parts), made a film, and composed aleatoric music (music involving chance and randomness).

This track is named for Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare, also known as the Large Glass (it is 2.7 meters, or more than nine feet, tall), in which he trapped various items between two large panes of glass, among them foil, wire, and dust. It has the appearance of a complex mechanism of uncertain purpose trapped between the panes of a large window. The original was broken during transportation, but Duchamp restored it, incorporating the shattered glass as part of the work.

Duchamp in a portrait by Man Ray (1920 or 1921) and his “Nude Descending a Staircase” (1912).

8. Opera

Zhao Shou (China, 1912-2003) No Wikipedia Entry

Zhao Shou is widely considered to have been the first surrealist painter in China. He attended the Guangzhou Municipal Art School and Shanghai Arts Academy, then studied at Nihon University in Japan in 1933, where he first encountered surrealism. In 1935, Zhao was one of the founders of the Chinese Independent Art Association, which was inspired by both surrealism and fauvism. He embraced surrealism, even translating selections from Breton’s Surrealist Manifestos, but also adapted it, insisting that it was not defined solely by Western artists. In the words of critic Mu Tianfan, he “believed that to paint surrealistically meant using Western techniques to express the Eastern spirit.” Zhao has no Wikipedia page, but details of his life and work can be found in an excellent paper by Chinghsin Wu, “Reality Within and Without: Surrealism in Japan and China in the Early 1930s,” which can be found on Academia.com, here.

This track is named for several of Zhao’s paintings, at least two of which are titled “Opera,” while still others incorporate visual elements of Beijing opera.

9. Ligne Bleu Clair

Simone Yoyotte (Martinique, circa 1910-1933) No Wikipedia Entry

Yoyotte was a poet and political writer from Martinique, and the first woman of African heritage to take part in surrealism, but very little is known about her. She was the sole woman in the Legitime Defense (“Self-Defense”) group formed in 1932 by Martiniquan students in Paris, and she published poems in the group’s journal—a publication that Léon Damas, one of the founders of the Négritude literary movement, called “the most insurrectional document ever signed by people of color.” She died in Paris aged just twenty-three.

There is no Wikipedia page for Yoyotte, but the few details known about her, and several translations of her work, appear in the excellent book on Black surrealism, Black, Brown, and Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora by Franklin Rosemont and Robin D.G. Kelley (Amazon.com link) and in the indispensable Surrealist Women: An International Anthology by Penelope Rosemont (Amazon.com link). There is also reference to her in a fictional setting in China Miéville’s novel The Last Days of New Paris (Amazon.com link).

This track is named for her prose poem “Ligne bleu clair dans un épisode de commande, j’ai troué le drapeau de la République,” which appears in an English translation titled “Pale Blue Line in a Forced Episode,” in Surrealist Women.

10. Sui Generis

Claude Cahun (France, 1894-1954) Wikipedia Link

Born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, Cahun was a gender fluid French photographer, sculptor, and author who, in 1917, adopted the name Claude Cahun, which in French is gender-neutral. In the novel Aveux Non Avenus, Cahun wrote, “Under this mask, another mask; I will never finish removing all these faces.” Suzanne Malherbe, who in childhood was Schwob’s step-sister, adopted the name Marcel Moore, and became Cahun’s lifelong partner and frequent collaborator. Cahun is best known for photographic self-portraits, sometimes appearing as female, sometimes as male, and sometimes as androgynous. During the German occupation of France in World War II, Cahun and Moore were active members of the anti-Nazi resistance. In 1944 they were captured and sentenced to death, but the area where they were held was liberated by the allies before they could be executed.

This composition is written in Cahun’s voice (as I imagine it), contrasting the commonplace idea of a woman as embodying a static, defined set of conventions with an alternative view of humans as layered, uncategorizable beings. Unlike most of these tracks, it’s not named for one of Cahun’s works, but, in a way, for all of them. Sui Generis is a Latin term, adopted into English, meaning “unique,” “without precedent,” or “forming its own category.” The idea that each person should define themselves rather than fitting into an preexisting category, no matter how loudly society objects, was a clear thread running throughout Cahun’s life and work—even when there was a war on and the people objecting were Nazis.

11. HexenTexte

Unica Zürn (Germany, 1916 –1970) Wikipedia Link

Unica Zürn is known as much for her difficult life as for her work, but this track is all about the work itself. In childhood, Zürn’s beloved father was absent, her mother was verbally abusive, and her brother was sexually abusive. As an adult, she experienced bouts of mental illness, loss of custody of her children, and romantic relationships that seem, from the outside, to have been unhealthy, and she eventually committed suicide. For all that, what matters is this: she created distinctive visual art and poetry, sometimes combining the two, with an immediately recognizable style of drawing, marked by fantastical, imaginary plants and creatures, and showed a facility with anagram poems, a particularly difficult form in which to work. In both these areas, her work is rooted in a powerful imagination and realized with a fanatical focus on detail.

This composition is named after her book Hexentexte (1954, “The Witches’ Texts”), which features paired poems and images.

You can find an excellent article on Zurn from the Paris Review, with illustrations and photographs, here.

12. C’est L’extase

Baya Mahieddine (Morocco, 1931-1998) Wikipedia Link

Born in Algeria, Baya (who chose to be known by her first name) was orphaned at age five, and was encouraged to pursue art by her adoptive mother. She was entirely self-taught. By age sixteen she had her first exhibition, at the Galerie Maeght in Paris in 1947, and was included by André Breton in the Second Surrealist Exhibition that same year. She has often been treated as a muse of Georges Braque, of Pablo Picasso (with whom she collaborated on pottery), and of Breton, all of whom admired her art, but more recently she’s begun to receive the recognition she ought to have had all along, as a major artist to be assessed on her own terms, full stop. Her first U.S. show was in 2018, twenty years after her death.

This track isn’t named after one of her works, but after the interplay between her paintings and her life. Baya created art that is insistently joyous, and when asked about it said that this was an intentional counterbalance to the unhappiness in her life. This dialogue is represented in the song, which is musically upbeat, but in which a woman asks herself doubtfully “This is extasy?” She answers her own question. “This is extasy,” she says, but her tone undercuts her words.

13. The Burning Giraffe

Salvador Dalí (Spain, 1904-1989) Wikipedia Link

Dalí probably has the highest profile of any artist associated with surrealism. His reputation has sometimes suffered under the weight of his grandiose showmanship, his avarice, and his questionable social views, and his imagery has been cheapened through endless bad reproductions hung on dorm room walls as stoner art, but underneath all the noise, his work remains what it always was: a fresh, potent, incorruptible corpus of art, executed nearly flawlessly, involving the rigorous conflation of the real and the feverishly imaginary, and marked by exuberance, on the one hand, and a subtle melancholy on the other.

This title of this composition comes from his painting of the same name, which is just the most prominent example of a motif that appears several times in his work: first in his film (with Luis Buñuel) L’Âge d’Or, then in another painting from 1937, Inventions of the Monsters, and finally in a much later work in watercolor and pastel, La Giraffe D’Avingon (1975).

You can see The Burning Giraffe and get more details about it here, Inventions of the Monsters here (click the image to enlarge it), and La Giraffe D’Avingon here.

You can watch L’Âge d’Or here.

14. Daughter of the Minotaur, Part I (A Slow Swamp Strut)

Leonora Carrington (England/Mexico, 1917-2011) Wikipedia Link

Leonora Carrington, a painter and novelist born in England, who spent most of her working life in Mexico, was one of the longest-lived and most prolific of all the surrealists. Her intensely potent paintings are marked by an interest in the subconscious, as well as in mythology. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, her work has begun to find a broader audience than it previously had, and she was the subject of a 2017 BBC television documentary, The Lost Surrealist.

Carrington has somehow managed to insist upon having two tracks to herself on the album—the only artist to have more than one. Both are named for her painting And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur! (1953). You can see the painting here.

15. Entre Tes Mots

Jean-Joseph Rabéarivelo (Madagascar, 1901 or 1903-1937) Wikipedia Link

Rabéarivelo was a superb poet from Madagascar who wrote in Malagasy, the national language, as well as in French, the colonial language, in some cases publishing his poems in two versions, one in each tongue. His influences were also dual, including French poets Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud, both of whom he translated into Malagasy, and French surrealism, as well as traditional Malagasy literature, which he translated in the other direction. He is known primarily for his poetry, although he also wrote novels, literary criticism, and an opera. When Madagascar gained full independence in 1960, he was declared its national poet.

This composition isn’t named after one of his works, like many of the others here. Instead it tracks Rabéarivelo in an imagined conversation with the long-dead Rimbaud, with whom he identified.

Jean-Joseph Rabéarivelo

16. Le Rêve Du Flâneur

Charles Baudelaire (France, 1821-1867) Wikipedia Link

Baudelaire was a French poet and essayist. He is widely considered–along with Arthur Rimbaud, Alfred Jarry, Isidore Ducasse (Comte de Lautréamont), and a few others–to be one of the “ancestors” of the dadaists and surrealists (while he, in turn, saw in Edgar Allen Poe an ancestor of his own). His best known work is the poetry collection Les Fleurs du mal (“The Flowers of Evil“), and his essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863), shaped the very idea of what a “modern” artist could and should be.

This track imagines the precise but dreamlike point of view of the “flâneur” or “flaneuse” (often translated into English inadequately as “idler” or “lounger”), who stands in a crowd, a fixed point in the middle of a vortex of human movement.

In his essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” Baudelaire describes the flaneur as a “passionate spectator”–an observer of human culture who is in their element in the urban crowd, and who feels at home everywhere. (The idea was later elaborated by critic Walter Benjamin, who distinguished the flâneur from the “badaud.” The former always retains his or her individuality, distinctiveness, and criticality, while the latter loses them in the mob.)

17. Canção Do Canibal

Oswald de Andrade (Brazil, 1890-1954) Wikipedia Link

Oswald de Andrade was a Brazilian modernist poet. He is best known for his Cannibal Manifesto, in which he reimagines the cultural relationship between Brazil and the colonial world. Rather than imitating European art, which would give it power over them, Brazilian artists should “cannibalize” it—internalize it, take ownership of it, and then create independent art that includes it without bowing down to it. In the post-colonial world immediately after World War II, the cannibalistic approach to culture became increasingly relevant, and it remains so now in a world where the dominance of U.S. culture is waning.

The title of this track references his Cannibal Manifesto, as well as the idea of consuming the world in order to possess and reinvent it.

18. Daughter of the Minotaur, Part II (A Roadhouse Stomp)

Leonora Carrington, see Track 14.

19. Piazza Shadows, Giorgio de Chirico (Italy, 1888-1978) Wikipedia Link

Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico is often treated as a surrealist, but he might be better thought of as one of surrealism’s antecedents, like Baudelaire (Track 5) and Alfred Jarry (Track 20). During his metaphysical period, he returned repeatedly to certain motifs, including images of public squares (piazzas) and elongated, late-afternoon shadows, creating a world that seems to exist in a single, endless moment of fading sunlight. His work was introduced to Paris by Apollinaire, and had a powerful influence on the surrealists.

This composition refers to the many iterations of shadowed piazzas in de Chirico’s work, and to the powerful emotional response they can evoke.

De Chirico and his painting La Tour Rouge, “The Red Tower” (1913)

More De Chirico: Le Mauvais Génie D’un Roi, “The Evil Genius of a King” (1914-15) (left) and Le Muse Inquietanti, “The Disquieting Muses” (1916-18).

20 Ubu Dit Au Revoir, Alfred Jarry (France, 1873-1907) Wikipedia Link

Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), like Charles Baudelaire and several other key artists (see Track 5) is widely considered to be one of the key ancestors of dada and surrealism. Jarry is best known for his play Ubu Roi, a satire on greed and power, and for his invention of the “discipline” of pataphysics. If physics deals with the concrete world around us, and metaphysics deals with things that are real but difficult to apprehend, pataphysics refers to the science of the purely imaginary—although its relation to science is likewise imaginary.

In this song Jarry’s most notorious creation, Ubu Roi, bids farewell, ending the album. He may be spouting nonsense, but along the way he insists, without compromise, on his liberty. “I am unbroken, I am free.”

Jarry in 1896 and his most notorious creation, Ubu.